Comparing how LGBT policy is addressed in Bermuda and Gibraltar

LGBT policies developed in different spaces vary greatly, with same-sex marriage currently legalised in only twenty-five countries.

BERMUDAGIBRALTARNEWS FROM THE OVERSEAS TERRITORIESRESEARCH

LGBT policies developed in different spaces vary greatly, with same-sex marriage currently legalised in only twenty-five countries. The justification for more inclusive policy stems from the fact that varying sexual orientations and gender identities are still subjects of discrimination. More people than ever are part of the LGBT community, yet seventy-two countries criminalise same-sex relationships and eight countries impose the death penalty for some homosexual acts. Why is this so? Globally, governments are not oblivious to the fact that there are alternative policy options. This article explains and assesses how LGBT policy is addressed in Bermuda and Gibraltar and asks why two British Overseas Territories (BOTs) have confronted it rather differently. The comparative method considers how LGBT policies differ between Bermuda and Gibraltar and why they diverge because of interests, institutions and ideas.

I consider the countries’ contexts and compare differences and similarities between Bermuda and Gibraltar in addressing LGBT issues, with particular focus on same-sex marriage. I attribute those differences and similarities towards interest groups, political parties and moral implications, drawing on cultural theory. Finally, I outline the observed effects of LGBT policy in these spaces, concluding that the comparison helps illuminate the influence of interest groups, political parties and moral implications towards LGBT policy, but other factors may be involved, and since Bermuda is the first country to repeal same-sex marriage, we do not know how this will impact global LGBT policy.

Bermuda and Gibraltar are BOTs that are politically, culturally and economically similar but diverge on LGBT policy, therefore we shall look to that difference to establish the reason for the divergence. Geddes (1990) states that to understand something, we must select one or more occurrences and subject them to scrutiny. Let us therefore focus on discrimination.

This comparison illuminates the understanding of policymaking in the rare example of Bermuda being the first country to repeal marriage equality, taking into account the fact that “when an anomaly is observed, it must be explained”. This locally concentrated anomaly holds problematic issues for international politics, tourism and human rights.

Bermuda

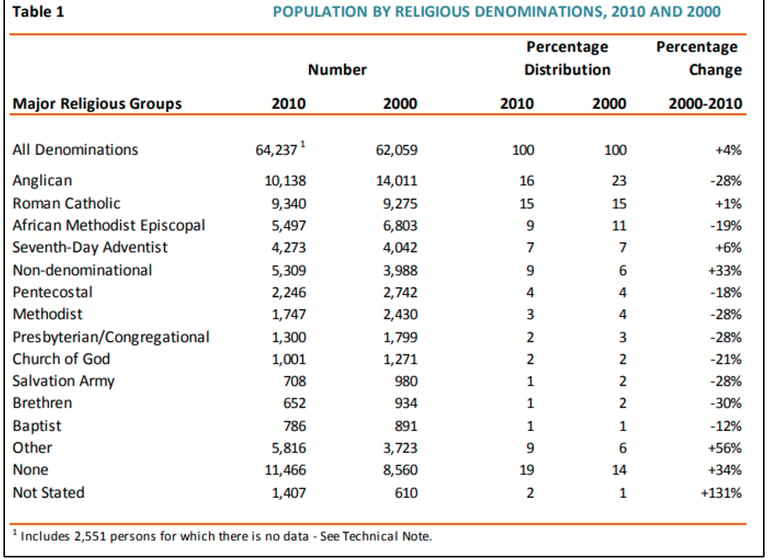

Contextual description and classification allows us to trace Bermuda and Gibraltar’s historical economic and constitutional development to provide empirical evidence. Bermuda is less than twenty-one square miles in size, lying some six-hundred miles away from North America. With a population of 64,237, it has a strong economy based around the international business and finance sectors and tourism, its primary sources of GDP. Claimed as a British colony in 1609, Bermuda is now a BOT. Bermudians are descended from Protestant colonists and African slaves. With a legacy of British colonialism, the island became home to Christian missionaries and evangelical groups and possesses one of the highest numbers of churches per capita in the world. Many citizens identify as Christian, with Anglican churches most prevalent. Over 75% of its population identify religious affiliations (Figure 1) and by extension is largely conservative. Bermuda has had a cabinet government with a premier since the 17th century.

Timeline of LGBT Policy

1994 – Stubbs Bill passed with vote of 22-16, decriminalising same-sex conduct, but with higher age of consent than for heterosexuals.

2008 – UK Foreign Affairs Committee declares that Bermuda’s Human Rights Act failed to criminalise discrimination based on sexual orientation or presented gender status.

2013 - Amendment to include sexual orientation passed.

2016 – Bermudians vote 2-1 against marriage equality in in public nonbinding referendum. Referendum invalidated as less than 50% of eligible voters turn out.

2017 – Same-sex marriage legalised: 1944 Marriage Act is ruled as inconsistent, constituting deliberate different treatment based on sexual orientation.

2018 – Progressive Labour Party (PLP) reverses right of marriage for same-sex couples. Governor gives royal assent to Domestic Partnerships Act. British government disagrees with decision but does not block repeal.

The timeline summarises how Bermudian LGBT policy has changed over the past three decades. Presently, Domestic Partnerships give same-sex couples rights “equivalent to those of heterosexuals”, however, these rights may not be recognised abroad. Heterosexuals can marry at sixteen with parental consent, yet same-sex couples must be eighteen to have a domestic partnership, and same-sex couples cannot dissolve their union based on adultery, yet heterosexual couples can use this as grounds for divorce in marriage. Global context dictates that this approach is not unique to Bermuda. Even in similarly developed countries such as Switzerland, marriage is reserved only for heterosexuals. In the USA, discrimination towards LGBT individuals is permitted in various states.

Gibraltar

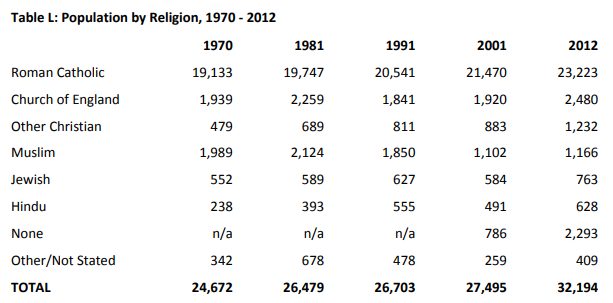

Gibraltar is three nautical miles wide and home to 32,194 people. Its financial intermediation sector generates the highest amount of national GDP followed by tourism. Gibraltar was a colony given to the UK by Spain in negotiations in 1713. It is the only BOT in the EU, and ethnically European. Over 70% of the population are Roman Catholic (Figure 2). Culturally, Gibraltar remained largely isolated, enjoying political and cultural solitude until its borders opened in 1982. Since the 18th century, it possesses a cabinet government with a chief minister.

Timeline of LGBT Policy

2000 – LGBT individuals allowed to serve in military.

1993 – Same-sex activity decriminalised.

2005 – Anti-discrimination laws in employment.

2012 – Age of consent equalised from 18 to 16 for same-sex partners.

2013 – Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas.

2014 – Civil Partnerships.

2016 – Same-sex marriage legalised under unanimous parliamentary vote.

Previously, there was no legal protection against same-sex discrimination in provision of goods and services. Eligibility for affordable housing schemes and visas did not extend to same-sex couples. Equal rights organisations felt systematically shunned by the government considering that the unequal age of consent was illegal under rulings by European Court of Human Rights. Along with this, discriminatory, homophobic criminal offences of “buggery” applied. Gibraltar has made significant changes in this area to tackle discrimination. Its geographical proximity to the UK has allowed British values and beliefs to contribute to Gibraltarian consciousness and identity. Despite an emphasis on religion, historically, moral considerations accompany the religious, with “every act subjected to ethical analysis, in terms of good and bad, of propriety, of doing the decent thing, of doing things by the book” wherein religions and races have lived harmoniously with one another.

Institutions, Interests, Ideas

The Foreign Affairs Committee (2008) raised the following issue amongst BOTs:

“We recommend that the Government should take steps to ensure that discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender status is made illegal in all overseas territories.”

The statement was directed towards both Bermuda and Gibraltar amongst others. Both countries have made considerable policy change since. Interest groups, political parties and moral implications have led the countries to respond to this shared issue in different ways. Both are members of the EU under auspices of the UK, and Bermudians and Gibraltarians alike are British nationals. However, the locality of the EU powerhouse with its emphasis on human rights has likely had a larger influence towards Gibraltar’s politics as opposed to the isolated island of Bermuda. The two developed countries have well-educated populations and an economy propelled by international business and tourism. They are self-governing democracies, with the UK having little say over their social policy. Culturally, they are not dissimilar, with both possessing large religious populations as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Despite the UK legalising same-sex marriage in 2013, historical legacy means that LGBT individuals continue to suffer under discriminatory effects of British colonial anti-sodomy laws in BOTs. The UK does not hold itself accountable for that discrimination as “[BOTs] are separate, self-governing jurisdictions with their own democratically elected representatives and the right to self-government”. However, the UK encourages policy learning towards LGBT citizens in the Commonwealth.

In 2016, Bermuda held a public referendum concerning same-sex marriage as opposed to Gibraltar, who ruled it out entirely. This highlights the problem of human rights as an issue for the public to vote on. Historically, discrimination issues such as inter-racial marriage were political problems – they were not subject to a public vote. It would have been considered an outrage if voters could decide whether black people could marry white people. The choice by Bermuda to hold a referendum reflects on its framing of LGBT problems as a debate topic, whereas Gibraltar has not seen them as appropriate grounds for a public vote.

Interest Groups

Interest groups are a major theme in explaining policy differences across our cases, which encompass two specific groups: equal rights activists and the Religious Right. Many religious Bermudians do not favour same-sex marriage, hence religious interest groups with homophobic tendencies are prevalent. The Church, as an institution and a collective, has publicly voiced its disagreement, with eighty religious leaders issuing a “Positional Statement” in response to same-sex marriage proposals:

“We continue to hold to the written Biblical position that same-gender sexual relations are against God´s standards for humankind - marriage is a holy institution.”

Eighty is significant in a small country where faith-based opposition influences national discourse. This is evident by the fact that the Registrar General granted charitable status to “Preserve Marriage Bermuda”, an anti-LGBT religious group. Equal rights activists termed this “a well-funded campaign of discrimination”. On learning that LGBT company “R Family Vacations” would be visiting Bermuda, the same eighty leaders responded that:

“We may just pick them (the passengers) up and bus them to our church, to different denominations, and have the pastors pray for them.”

The company no longer includes Bermuda as a destination, propelled by the “Boycott Bermuda” movement in which hashtag #boycottBermuda appeared numerously on Twitter. Bermuda registered ships will be banned from holding same-sex marriages at sea. Interest groups worldwide have influenced Bermudian policy, including US-based right-wing anti-LGBT “National Organisation for Marriage”, which advised Bermudian religious groups on marriage preservation strategy in the lead-up to the referendum. Conversely, not all Bermudian religious communities advocate against LGBT individuals - Wesley Methodist Church openly welcomes them. However, this is unusual, and Bermuda’s religious following tends to oppose policy change in favour of LGBT individuals, which wealds significant influence over Bermuda’s policy choices.

Pro-equality supporters have actively addressed this opposition. Activist group “Two Words and a Comma” was created by PLP Minister Webb in 2006 to protect Bermudians from same-sex discrimination after her proposal to outlaw LGBT discrimination was ignored by parliament. Equal rights group “Rainbow Alliance of Bermuda” has held rallies drawing thousands of supporters including Amnesty International Bermuda. Although various international interest groups supported the repeal, in the same vein, some international groups called to veto it, with the US Human Rights Campaign calling it “deplorable”. Clearly, both religious groups and equal rights groups maintain solid campaigns towards Bermudian LGBT policy. I will explain how this significantly impacts party politics surrounding the issue.

In contrast, Gibraltar’s more inclusive approach has made it popular as a same-sex marriage location with the government developing new ideas and products aimed specifically at LGBT markets. Gibraltar has received international support towards the LGBT cause through ILGA Europe, which advocated to bring Gibraltar in line with European human rights standards. Bermuda’s “Rainbow Alliance” can be likened to Gibraltar’s “Equality Rights Group” (ERG). ERG has drawn attention to the conscience clause within the Gibraltarian same-sex marriage bill allowing registrars “not to officiate same-sex marriages if they violate their religious beliefs”. This is certainly an idea for Bermuda that may appease both LGBT individuals and religious groups.

Like Bermuda, Gibraltarian religious leaders have not been fully supportive of new policies, with one leader stating that “it is a mistaken, laudable notion, that equality should be the cornerstone of any human endeavour”. Gibraltar’s Christian and Jewish community, particularly the “Evangelical Alliance”, argued that proposals were driven by political correctness and would destroy society. ERG (2016) responded that:

“the Bishop will defend his religious and institutional precepts as are his right…ERG and secular society will do the same on their side”.

In contrast to the large “Preserve Marriage Bermuda” group, Gibraltar’s equivalent, “In Defence of True Marriage” has only twenty members and was promptly apprehended by the Chief Minister over Twitter after they deemed homosexuality as a handicap. This highlights how Gibraltar’s government publicly disagreed with religious opposition to new LGBT policies, whereas the Bermudian government used faith-based opposition as an instrument to retain favour with religious voters and others possessing more traditional views.

Political Parties

How were these interest groups able to influence their governments, and therefore the policy process? Political context helps make sense of national similarities and differences by eliminating and identifying factors to build a theory. Under PLP governance in 2008, Bermuda was the only BOT not to join a human rights initiative arranged by the Commonwealth Foundation. Most PLP ministers oppose LGBT rights, with aforementioned Minister Webb being quite the exception. In 2011, the party was succeeded by the One Bermuda Alliance (OBA). One reason might lie in PLP’s alienation of LGBT citizens. OBA added sexual orientation discrimination to the list of prohibited grounds of discrimination in the Human Rights Act, followed by the 2016 Civil Union clause, which received no support from PLP opposition. Soon, marriage followed.

The Governor’s Throne Speech on behalf of the OBA stated that:

“Bermuda does not have [justice and equality] and it is to our collective discredit as a democratic country in the 21st Century…we [must] address protection against discrimination for a range of characteristics including sexual orientation.”

PLP was re-elected in 2017. This is not unprecedented – polls predicted that OBA would lose support from men, blacks, PLP supporters and the highly religious if it spearheaded legalising same-sex marriage. PLP has used same-sex marriage as an instrument, promising that if elected in 2017, it would reverse same-sex marriage, and subsequently voted 24-10 against it. Minister Brown stated that “[the repeal] is being done for one simple reason. The status quo, which allows for same-sex marriage, is embraced by one segment of the community; it is not embraced by another”. A 2015 poll backs this up, showing that 48% of Bermudians supported same-sex marriage whilst 44% did not. This shows how Bermudian parties acted as arbiters between various interest groups to supply specific policy outcomes.

One consideration is that religious groups actively opposed same-sex marriage, therefore the PLP encouraged this opposition as part of its wider agenda of morality politics to gain political power.

Gibraltar’s political arena is quite different, and has been led by the Socialist Labour Party (SLP) since 2011. Before this,

LGBT policy made little progress under the Gibraltar Social Democrats (GSD) who headed parliament. Equal rights group “OutRage” accused GSD of state-sanctioned homophobic discrimination claiming that it was out of touch with social progress in the rest of Europe. ERG similarly challenged the party:

“The government’s only recent commitment has been entirely negative and hostile. It has stated that it will only introduce reforms where it is legally compelled to do so.”

ERG existed for seven years by this point, but was one of the few community organisations receiving no government funding or premises, despite providing a valuable community service. ERG approached the European Commission to voice its disagreement with the party. Currently elected party SLP took up ERG’s demands in its election manifesto, taking over from GSD in 2011. In 2013, SLP amended the Crimes Act 2011 and now considered same-sex harassment as a hate crime. Since taking over, SLP has initiated “International Day Against Homophobia” rallies. In contrast with their past policy choices, the leader of preceding party GSD announced support for same-sex marriage in 2016. The government legalised same-sex marriage that year with unanimous support from all fifteen members of parliament. Since the majority of Gibraltar’s political parties support LGBT rights, it contrasts greatly to Bermuda, headed by an anti-LGBT party. I will explain how beliefs structured this political activity, wherein the interest groups considered were created out of these ideas.

Moral Implications

BOTs possess complex bilateral relationships and cultural diversity, making it difficult to foster and embed reform. Gibraltar and Bermuda possess unique cultures exhibiting different beliefs. Interest groups are based around those beliefs that “help explain why particular courses of action are taken”.

In Bermuda, tradition propels the idea of homosexuality being a sin. If we consider that ideas “shape the selection process between available alternatives as well as how past policies and institutions limit the choice at hand”, we see how religious groups and their ideas of tradition influence current policies. A fear of repercussions exists amongst families for those who expose LGBT members, with some Bermudians admitting they face opposition from their family. In 2006, the PLP attempted to prevent LGBT advocate Mark Anderson from participating in a parade, stating that he challenged local values and sensitivities. PLP Premier Bean claimed in 2013 that gay marriage would lead to moral disruption on live television, stating that the purpose of gay marriage is to turn “civilisation upside down” and attack the family unit.

It is reasonable to assume that Bermuda’s isolation has helped retain these beliefs as opposed to Gibraltar, with borders in Europe that have allowed ideas from surrounding countries to spread and exert influence there since 1982, when said borders were opened:

“This long economic, physical and psychological blockade meant that we were left with little opportunity for new ideas and movements happening in the rest of Europe to filter through.”

Since its borders opened, Gibraltar has swiftly adopted the ideas of surrounding countries, considering it only took thirty years since the border opening for Gibraltar to implement same-sex marriage. This does not mean every member of Gibraltarian society agreed with those ideas; in 2008 some Gibraltarians expressed that LGBT rights were “an attempt to bring in extraneous standards from other places in Europe that cause the breakdown of the family and society”. However, ERG encouraged LGBT people not to be “intimidated by the custom of past influence”. As noted, Gibraltar’s government publicly shut down homophobic statements, which tells us that if opposition does exist, it likely remains unexposed due to the knowledge that homophobia is rarely tolerated, rather than in Bermuda where we have seen the PLP government encourage anti-LGBT views to further its own agenda.

Effects of Policy

We have seen whose preferences were ultimately enacted in each state. LGBT policy is a new area and the transfer literature is not extensive. There was no solid method to test whether Bermuda was an appropriate country within which to implement same-sex marriage. Both countries are religious and view homosexuality as a sin. We must therefore look beyond religion and towards social and cultural influences. Other countries, such as Portugal and Spain, are Catholic but still legalised same-sex marriage in the same way Gibraltar did. Perhaps this gave influence to Gibraltar, a nearby country, and not Bermuda, located much further away.

Some observed results of Bermuda’s LGBT policy choices include pessimistic views of the Bermudian government, with individuals viewing themselves as second-class citizens. Resultantly, some Bermudians have chosen to live abroad rather than stay somewhere they would not possess equal rights. Labour MP Chris Bryant echoed this notion:

“It’s a backward step for human rights in Bermuda and in the overseas territories…gay and lesbian Bermudians told that they are not quite equal to everyone else and that they do not deserve the full marriage rights that other Bermudians enjoy.”

Bermuda’s tourism is predicted to suffer, with cruise companies considering re-registering ships in more LGBT-friendly locations. The repeal may be considered policy failure considering these effects, especially as no other government has made such a repeal. Gibraltar, with its more inclusive policy, has been successful in growing its tourism as a result. It has consistently had an equal rights government for some time, which took to social media to openly defend LGBT individuals from discrimination. The implementation of a conscience clause within same-sex marriage shows that both LGBT individuals and religious groups have had their views considered. Gibraltar is globally considered to be progressive, and the conscience clause is holistic in that should a religious leader refuse to officiate a same-sex marriage, an alternative registrar must be assigned. A satisfactory outcome is possible.

Even though both countries have adjusted their equality laws in the twenty-first century, gender identity is still not recognised and gender cannot be changed.

We have examined two countries faced with a similar policy problem. The policies implemented by each one varied greatly, with Gibraltar becoming an international hotspot for same-sex marriage, and Bermuda becoming internationally boycotted by equal rights activists after repealing same-sex marriage. Although the literature and this writing itself cannot entirely explain why these policies were adopted, the observations made lend themselves to a wider debate. The comparison has built an overall conclusion that Gibraltar is more progressive than Bermuda in solving LGBT policy issues because of geographic proximity to similarly progressive countries and the government’s rebuttal of anti-LGBT tendencies and active promotion of LGBT opportunities. In contrast, isolated Bermuda has experienced differentiated electoral outcomes, with a pro-LGBT and an anti-LGBT party both in control of its government at different points in the last two decades. As a result, parties have used LGBT policy as an instrument to win favour from voters influenced by religious groups and culturally embedded tradition. These cases may help understand and explain LGBT-related social phenomena, something requisite to improving people’s lives. For now, we must wait to see whether other countries will follow Bermuda’s example.