Focus: Britain's Sovereign Base Areas

The Sovereign Base Areas (SBAs) are technically British Overseas Territories, occupying 99 square miles on the island of Cyprus and serving as platforms for British military operations in the wider Middle East.

AKROTIRI & DHEKELIARESEARCH

The Sovereign Base Areas (SBAs) are technically British Overseas Territories, occupying 99 square miles on the island of Cyprus and serving as platforms for British military operations in the wider Middle East. They were established around Britain’s existing military bases when Cyprus was granted independence in 1960, in addition to several non-sovereign “retained sites” - military bases which Britain is allowed use of - on the island, such as the radio monitoring station on the summit of Mount Olympus in Cyprus’ scenic Troodos Mountains.

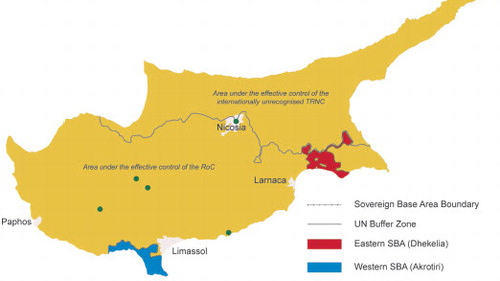

Map showing the SBAs, UN Buffer Zone, and retained sites in Cyprus

The bases are home to around 8,000 military personnel, staff and families, but also approximately 7,000 Cypriots in 24 villages across both base areas. There is well-paid employment to be found on the bases for Cypriots, but the bases have also seen protest on issues from radiation emitted by communications towers to their military operations in Syria (for example air strikes launched in April 2018 on Syrian government military targets). Thus, the bases are a contentious issue, especially when considered in the wider context of the Cyprus Issue, with Britain being seen as a divide-and-rule imperial power by both sides of the Greek-Cypriot/Turkish-Cypriot impasse.

Research

To investigate further the issues presented by the SBAs within the context of the Cyprus Issue, a team of four geography undergraduates from Newcastle University set out to explore the views of a key peace building actor on the SBAs - that of civil society. Because the Cyprus Issue has been at an impasse for nearly 50 years, international actors vested in solving the solution such as the EU and UN - which maintains a peacekeeping force on the island - are increasingly turning to civil society as a force for reconciliation and long-term peace building on the island. This means that civil society will have a greater input into two key areas - the formal peace process, with committees set up by the UN on reconciliation such as the Committee on Missing Persons increasingly being civil-society led, and public opinion, as bi-communal activities form a key aspect of the UN’s long-term peace building strategy.

The project conducted semi-structured interviews with 8 civil society organisations, ranging from bi-communal citizens’ groups to youth charities promoting reconciliation, exploring their views on the international actors role in peace-building in Cyprus, with the SBAs one of the actors focused on. The EU, UN and SBA offices in Cyprus were also interviewed to gauge their perception of the international actors’ role in peacebuilding. The results for the SBAs were decidedly negative, with all civil society organisations taking a negative view of the bases. One issue raised was the perceived neocolonialist presence of foreign military bases on the island of Cyprus, that stoked the anti-imperialist sentiments towards the wider British presence in Cyprus among Greek Cypriots, who resented the previous refusal to grant union with Greece (enosis) in the 1950s and divide-and-rule tactics towards the two communities during the armed revolt in that period. The other main objection towards the SBAs was their operation in the Middle East potentially endangering Cyprus, with air strikes carried out during the Iraq War, Libyan Intervention, and Syrian Civil War. One activist remarked:

“What would have happened if Gaddafi decided to send us a gas bomb or something? Is Britain going to protect us? No. What would happen if Saddam would send a rocket to our capital? Who is going to protect us?

This exemplified a wider dislike of foreign interference in the affairs of Cyprus, as there was also dismissal of the effectiveness of the UN peacekeeping force in Cyprus. The conclusions of the project are clear, that on a level of principle and practicality, Cypriot civil society sees the SBAs as an unnecessary infringement on Cyprus’ sovereignty and a threat to its security.

Future

Future developments around the SBAs are complex, and bound up in the twin spectres of the Cyprus Issue and Brexit. Regarding the former, as part of the rejected Annan Plan of 2004 to reunify the island, the UK had agreed to return 45 square miles of the SBAs’ territory to a reunified Cyprus, consisting of agricultural land and not the military bases. This may have played a part in the rejection of the Plan by Greek Cypriots in a referendum by 76% to 24% (incidentally, Turkish Cypriots voted in favour of the Plan by 65% to 35%, though it required approval from both communities to be implemented), as the existing security structure of guarantees and the SBAs is deeply unsatisfactory the Greek Cypriot community. In an interview during the above project, the Chief Civilian Officer of the SBAs reiterated that this offer remains on the table, to sweeten any deal struck between the two communities with a view to reuniting the island.

Britain’s exit from the European Union may have an effect on the SBAs, as they do not form part of the European Union yet mirror EU law under an agreement between the UK and Republic of Cyprus, allowing agricultural goods from the SBAs to enter the EU freely. This may be thrown into jeopardy by a no-deal Brexit, as the provisional Withdrawal Agreement creates a customs union between the SBAs and Republic of Cyprus which would not come into force if the UK leaves the EU without a deal. The SBAs also border the self-declared and internationally-unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, and operate passport and customs checks between the two - this would become an EU external frontier upon Brexit, which would require extra customs checks on Northern Cyprus goods when entering and exiting the SBAs.

The future for the SBAs is thus unclear - in the face of protest and opposition from Cypriot civil society, and with political uncertainty from Brexit and the possible resolution of the Cyprus Issue, the UK will have to continue to justify its presence on the island of Cyprus. Despite this seemingly perfect storm of issues, creative solutions may be able to overcome the problem, for instance ceding the bases to the Republic of Cyprus and then renting them back, their use being subject to the Cypriot parliament’s approval. Britain must decide whether it prioritises the sovereign use of the SBAs or the consent of those endangered by their operations.