The Falklands and its path to self-determination

This articles provides an overview of the background of the Falkland conflict, its consequences, and ongoing diplomatic challenges.

FALKLAND ISLANDSRESEARCHNEWS FROM THE OVERSEAS TERRITORIES

The Falkland Islands’ path to self-determination has been anything but smooth. Though brief, the 74-day conflict between Britain and Argentina over the islands left a lasting mark – on both the Islanders and those who fought. Currently, similar geopolitical tensions arise where enduring claims collide with ongoing struggle for self-governance in contested regions.

The Conflict

At 6am on the 2nd of April 1982, the quiet of Stanley Harbour was shattered by grenades and rockets launched by Argentine special forces. As shockwaves rolled through the northern ridge, Major Phil Summers addressed the forty-strong civilian militia tasked with defending the island: “Right lads, it's started.”

Like many Falkland Islanders - or ‘Kelpers,’ as they nicknamed themselves - Summers had long expected tensions with Argentina to reach a boiling point. Still, the invasion came as a shock to many on the islands.

Before the conflict, the British government had planned major defence cuts, including military withdrawal from the South Atlantic. Sensing vulnerability, Argentina launched an invasion, believing Britain’s reduced presence would ensure an easy victory. Facing domestic turmoil, the military junta sought a decisive victory to unite the nation and deflect attention from unrest at home.

The invasion was quick at overwhelming the small British garrison at Port Stanley, leading to a swift occupation. Argentine forces took control of the capital, and settlements such as Goose Green, detaining some civilians for weeks until British troops arrived. While Argentine soldiers largely adhered to military conduct, their looting and mistreatment of conscripts left a lasting impression on the Islanders.

Britain responded immediately, declaring a 200-mile exclusion zone around the islands.On the 5th of April, a naval task force set sail, led by aircraft carriers the HMS Hermes and the HMS Invincible, and repurposed cruise ships carrying troops. The 8,000-mile journey posed logistical challenges, with the armed forces utilising Ascension Island as a forward operating base. The war proved costly, with nearly 1,000 lives lost, including three civilians killed by shrapnel.

For the Islanders, the occupation was defined by fear and uncertainty, though Argentine troops largely followed military conduct. Homes were searched, food supplies dwindled, and movement restricted. In the conflict’s final stages, local farmers helped British forces transport supplies to the front lines. Meanwhile, some civilians engaged in small acts of resistance against occupying troops. Many of them remain deeply grateful for the sacrifices made in retaking the Falklands.

Though Stanley was spared from direct combat, fear loomed over its inhabitants daily. “After the war, when we got back to our home, all the family heirlooms had been destroyed by the troops who had occupied it,” recalled Bonnie Greenland, who had fled Stanley. Others, like nurse Rachel Aspogard, noted that returning home was further delayed by booby traps left behind by retreating forces.

Over 30,000 landmines were planted across the islands’ beaches and farmland, only cleared in 2020. As Graham Bound recorded in Invasion 1982: The Falkland Islanders’ Story, “the images from those days were horrible, sad, and frightening […] embedded deeply in the clay of many minds”.

On the 14th of June 1982, Argentina surrendered, restoring British administration. The defeat shattered the credibility of Argentina’s ruling junta, leading to mass protests. By 1983, the dictatorship collapsed, and democracy was restored. In the UK, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher used the victory to revive national pride, and secure her party a landslide victory at the subsequent 1983 election.

For the Islanders, the war was more than a political event; it was a pivotal moment in their fight to determine their own political future in the protracted sovereignty debate.

Historical Background and Rising Tensions

Territorial disputes have long been a major source of interstate conflict. After World War II, decolonisation and the emergence of new states intensified tensions. Islands, once valuable for imperial trade, became even more significant when maritime laws changed in the late 1960s. Nations could now claim 200-mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs), granting them control over surrounding resources. This made remote islands, especially those with potential oil reserves, highly valuable.

In the case of the Falklands, sovereignty disputes date back to the 18th century, with competing claims by Britain, France, and Spain, leading to the islands changing hands frequently. English mariner John Strong first had sight of the islands in 1690, naming the sound between them after the 5th Viscount of Falkland, but France established the first settlement in 1764 before ceding it to Spain. Sources indicate that prior to settlement, there had been no permanent indigenous population in the islands.

In 1770, the Spanish expelled the British, bringing them both to the brink of war. Although Britain was later permitted to return, they withdrew in 1774, leaving behind a plaque to reaffirm sovereignty. Spain maintained control until abandoning the islands in 1811. After Argentina declared its independence from Spain in 1816, they claimed the islands as part of their national territory. In 1833, Britain reasserted its sovereignty expelling Argentine forces.

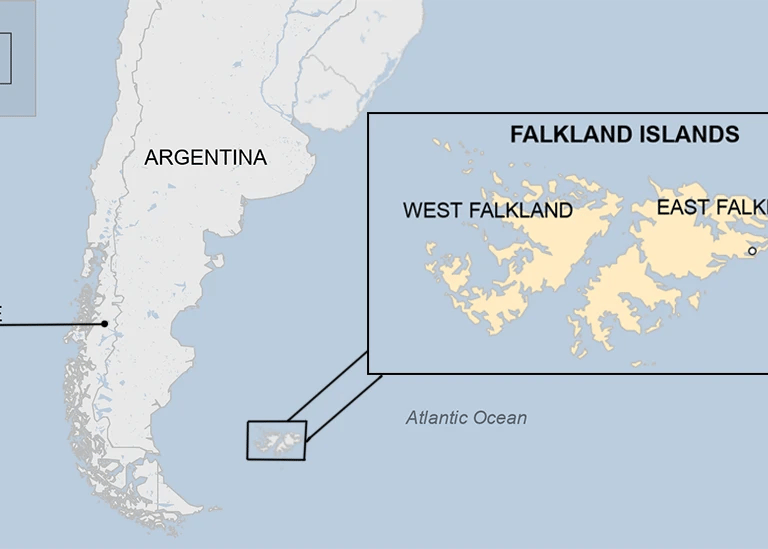

Geography is also central to Argentina’s claim, as the islands are located just 300 nautical miles off its coast. This proximity, along with attaining Spain’s prior rule, forms the basis of Argentina’s constitutional claim.

However, Britain has administered the islands for nearly two centuries. The population, primarily of British descent, traces its lineage back nine generations. Aside from foreign affairs and defence, the Falkland Islands are self-sufficient and self-governing.

This raises the central question: Should territorial disputes be settled based on historical claims or the will of the people who live there today?

Self-Determination and the Referendums

The principle of self-determination enshrined in the UN Charter asserts that people have the right to choose their political status. Since 1946, the Falklands have incorrectly featured on the UN’s list of non-self-governing territories. In 1965, UN resolution 2065 called for Britain and Argentina to negotiate a resolution. Decades later, no settlement has been reached.

Diplomatic relations remain strained, with Buenos Aires insisting on bilateral negotiations with the UK, and refusing to acknowledge the existence of the Falkland Islands Government or elected representatives. Some progress was made when Argentine President Carlos Menem’s leadership, in 1989, led to restored ties in 1990, followed by discussions on fishing rights and oil exploration. Still, Argentina’s broader claim over the islands has ensured tensions persist to this day. Recently, the Argentine government withdrew from the Foradori-Duncan Pact of 2016, which regulated shipping and fishing around the islands and the extraction of oil and gas, as well as setting up a process to identify who had died on the islands during the Falklands War. At the same time, they demanded talks on sovereignty.

International organisations such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), the Southern Common Market, and the Organisation of American States (OAS) have previously backed Argentina’s position. However, Britain maintains that sovereignty talks cannot occur unless the Falkland Islanders themselves choose to engage.

After the conflict, Falkland Islanders have exercised this right through democratic referendums. In 1986, 96% voted to remain British. In 2013, a second referendum reaffirmed their stance, with 99.8% voting to retain their status as a British Overseas Territory.

During the year of the second referendum, Argentina’s then-President, Cristina Fernandez de Kirschner, took a case to the UN’s C-24 Decolonisation Committee, imploring the UK to negotiate. Once again, the UK refused.

Economy and Developments

Meanwhile, the Falklands’ economy thrives, largely due to fisheries and a growing tourism sector that attracts up to 60,000 visitors annually. Notably, the Falkland Islands Museum and National Trust, founded in 1991, which promotes education and local heritage.

Further, in an effort to engage Argentina in friendly fishery, Britain declared a unilateral fishery zone in October 1986. The Falklands Interim Conservation Zone (FICZ) boosted their government’s total income from £6 million in 1985-6 to £35 million in 1988-9.

The UK Government has also invested in infrastructure, including schools, jetty upgrades, and air defence systems, with other projects, such as a new power station and runway repair works, currently underway.

Despite diplomatic tensions, British policy remains guided by the Islanders themselves. Their population has doubled since the war, with over 60 nationalities represented. In 2024, former UK Government Minister Lord Tariq Ahmad reaffirmed the UK’s stance at the OAS General Assembly: “Our resolute support for the Falkland Islanders’ right to self-determination remains unchanged. Only they should decide their future” a pledge the current, and all former UK Governments have made since the war.

Future Concerns and the Chagos Precedent

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s decision to transfer sovereignty of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius and end “outdated practices” has reignited calls from Argentina for negotiations over the Falklands. Argentine Foreign Minister Diana Mondino posted on X that if Britain could negotiate over Chagos, it should be open to discussions about the Falklands and Gibraltar.

However, the UK Government maintains that the Chagos Islands are a distinct case, and do not believe comparisons to other UK Overseas Territories should be drawn. Unlike the forcibly displaced Chagossians, the Falkland Islanders have continuously inhabited and governed their land for generations.. On the day of the Chagos deal, and amidst some uncertainty on the islands, HE Alison Blake, Governor of the Falklands, reassured her countrymen that the “legal and historical contexts of the Chagos Archipelago and the Falkland Islands are very different”.

This article reveals a whistle stop tour of the background of the Falkland conflict, its consequences, and ongoing diplomatic challenges. As global politics evolve, sovereignty debates will persist, but one fact remains unchanged -the voices of the Falkland Islanders must be at the heart of any discussion about their future. In their official website, the Falkland government cements their wishes for the inhabitants’ right to self-determination. As Leona Roberts, manager of the Falkland Islands Museums, succinctly states, the Islanders are a distinct people and are “proud to be Kelpers’’.

The FOTBOT committee will be visiting the Falkland Islands from the 17th to the 21st of February, and looks forward to engaging with local people.

The sinking of the Royal Navy frigate HMS Ardent

City of London's Salute to the Task force, marked the retaking of the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands Profile

Subsequent damage to a house in Stanley

Lieutenant Alfredo Astiz signing the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of all Argentine forces at Lieth, on South Georgia on board HMS Plymouth

A cruise ship and squid trawler in Port William, Falkland Islands, from the site proposed for a new deep water port development