The Forgotten Voices of the Chagos Archipelago

Many who were born in the Chagos Archipelago have died in exile, holding onto hope for a return. Their absence does not mean silence. Those who remain carry their legacy, and we deserve to be heard.

NEWS FROM THE OVERSEAS TERRITORIESBRITISH INDIAN OCEAN TERRITORY

Many who were born in the Chagos Archipelago have died in exile, holding onto hope for a return. Their absence does not mean silence. Those who remain carry their legacy, and we deserve to be heard.

This is my grandmother, Panselia. Her smile hides the pain of a lifetime lived in exile.

East Point, Diego Garcia: a place most people have never heard of, yet it was once home to a vibrant island community within the Chagos Archipelago. A quick online search reveals that East Point “served as the administrative capital until the depopulation of the territory,” according to Wikipedia.

For many of those forced to leave — and for their descendants scattered across Mauritius, the Seychelles, the UK, and beyond — the dream of one day returning has never faded.

But now, as the question of the islands’ future returns to the political stage, that hope is once again overshadowed by a familiar frustration: the future of their homeland is being decided without them. On May 22nd, the UK Prime Minister announced an agreement to hand over the sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius (UK Government, 2025).

Decades later, after the forced displacement of this population, the future of the archipelago is being decided in distant capitals and signed off on virtual screens — while descendants of the displaced march through the streets, still fighting to be heard.

If parliament approves Keir Starmer’s decision, the Chagos Archipelago will disappear from the map of the UK’s overseas territories. The British Indian Ocean Territory will vanish into thin air. For those who believe in the power of this flag, it is another hard blow. But who really cares?

Thanks to a long-term agreement, the United Kingdom will secure the future of a joint UK-US military base at Diego Garcia. This will cost £101 million per year to UK taxpayers. The net present value of payments under the treaty is estimated at £3.4 billion (UK Government, 2025).

While governments exchange billions and negotiate power, the people who paid the real price are still waiting for justice. It is a significant deal for Mauritius, but what about the surviving indigenous people and their descendants?

East Point: The island where my grandmother was born

Behind these billion-pound agreements and virtual diplomatic handshakes lie many untold stories. These are the stories of those who were never allowed to return. The Chagos Archipelago is more than a chain of atolls, and Diego Garcia is far more than a military base. For me, this territory holds deep personal meaning. East Point is not just a dot on the map. It is where my grandmother, Panselia, was born.

According to the Chagossian Records, her mother, Regina, was also born in the archipelago, specifically in 1902 on the island of Pointe Marianne. That was over 123 years ago. At the time, the Chagos Archipelago and Mauritius were administered as part of the Crown Colony.

When the era of independence arrived, Mauritius was given the opportunity to choose its own future — to become a sovereign nation. Chagossians were not given that choice. Instead, they were uprooted and exiled from their homeland. One people gained a country; the other lost everything. While Mauritius moved forward as a new nation, the Chagossians were dispersed, silenced, and denied a voice in the fate of their islands.

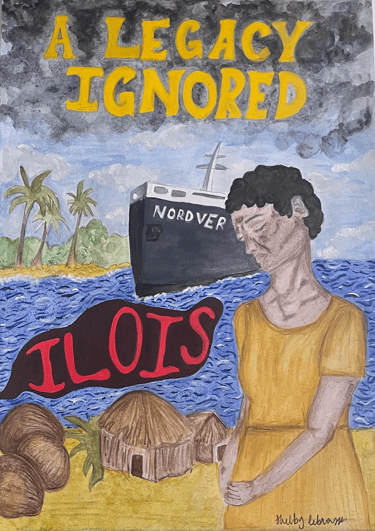

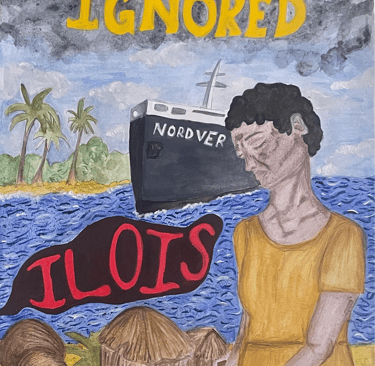

“Ilois”: A label that stings

It is crucial to recognise that many Mauritians today celebrate and assert that the Chagos Archipelago has always been a part of Mauritius. Yet many Chagossians were not seen as valued members of Mauritian society — often referred to simply as ‘Ilois’, generally translated as “islander”.

In Mauritius, where everyone technically lives on an island, calling someone Ilois was rarely just a neutral label. Growing up, I came to feel the subtle sting behind that word. Too often, it came with a quiet condescension — a reminder that we are tolerated outsiders.

It’s strange how a simple term can carry so much weight and echo with exclusion even when wrapped in familiarity. In this context, being an Ilois or Iloise isn’t just about geography but dignity and memory.

She survived — But she never stopped longing

My grandmother survived until the age of 75. The verb “survive” is used intentionally here to grab the essence of her difficult life. Ever since she was denied the right to return to East Point, her birthplace, a profound void settled in her heart — a wound that never fully healed.

I still remember the look on her face when she leaned against the sink in her small kitchen, completely lost while waiting for her “Seraz” to be ready. I felt that the aroma of that traditional dish transported her back to her island, perhaps to some childhood memories of happier and simpler times. Although she rarely spoke about her feelings regarding her lost island, she often shared her desire to return there to spend her final days.

Until her last breath, she held on to the incredible hope of seeing her island again. Sadly, she never had that chance. Two decades have passed, and her disillusionment will not influence political decisions. Once again, history is set to repeat itself. Her grandchildren are still referred to as “Ilois and Iloise.”

A Voice for the Exiled

In the 1960s, politicians plotted the fate of my grandmother’s island, leaving her with no say in a decision that would forever alter her life. Now, in 2025, her grandchild and her great-grandchildren are being denied the right to have a say in the future of our ancestral land.

As a descendant of this resilient heritage, I demand recognition as a vital stakeholder in determining the future of the Chagos Archipelago because our stories and our lives deserve to be at the forefront of these conversations.

My mother was born in exile, and like many children and great-grandchildren of displaced women, I emerged into this world in Port-Louis. With a Mauritian father and Chagossian roots, I carry both histories in me. This identity wasn’t something I chose — it’s something I inherited. And I won’t be made to deny any part of it.

I now live in the UK, not as an outsider, but as a citizen. I’m not an illegal immigrant, and I deserve to be treated as such. Asking us to let go of one part of ourselves only mirrors the same injustice that fractured our families apart in the first place.

My grandmother may be gone, but I am here. Her voice will never be forgotten.

Last weekend, many people came together to oppose the transfer of the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius. Like me, they likely wanted to represent the voices of their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents.

This isn’t just politics for me — it’s personal. I often think of my grandmother. It would have broken her to see that, as they did in the 1960s, statesmen are deciding her island’s future. The fate of her beloved island should not be dictated behind closed doors by leaders like Keir Starmer, Navin Ramgoolam, or any group of politicians. She would be proud to see me speak up to reclaim the right to have a say in the future of her native land.

Speaking up for her — and for our history — is my way of showing love and refusing to stay silent.

A future we deserve a say in

Chagossians, natives and descendants, we are at a turning point in our fate. Let’s stand up for our ancestors and future generations so they are no longer afraid to speak up for their rights.

The stories and struggles of our ancestors make us more resilient, so let’s fight to ensure our voices are heard. We need to be actively involved in the conversation. We must not let the future of the Chagos Archipelago be written without its people. We are the heirs to this history, and we deserve a seat at the table. Our past was stolen — our future must not be.