The Lords must block the Chagos deal - there is another way

Evidence, not ideology, shows the Chagos Islands can be restored, but only if Britain has the will.

NEWS FROM THE OVERSEAS TERRITORIESBRITISH INDIAN OCEAN TERRITORYOPINION

On Tuesday, the Government quietly withdrew the committal motion for the Diego Garcia Military Base and British Indian Ocean Territory Bill, preventing peers from voting on Lord Callanan’s amendment to delay the measure while ongoing legal challenges conclude. It was a tactical retreat, and an admission that Ministers risked defeat in our upper House.

Yet this pause is temporary. The Bill, which would pave the way for handing the Chagos Islands, one of the fourteen British Overseas Territories, to Mauritius, will almost certainly return. And when it does, peers must stop it.

The Government has misrepresented the legal and moral position of the islands, claiming that it has “engaged” with the Chagossian community while lending false legitimacy to Mauritius’ spurious sovereignty claim, which is only rooted in an administrative technicality from before independence. The Chagos Islands have been British for more than two centuries. Despite being forcibly removed from the islands by Britain between 1968 and 1973, the majority of Chagossians remain loyal to the Crown and still hope to return home. The Bill would extinguish that hope and sever a vital link in Britain’s security network.

But the case against the handover is not just emotional, but empirical. The Government’s own evidence proves that resettlement of the islands under continued British administration is both possible and affordable.

In 2014, the British Indian Ocean Territory Administration commissioned KPMG to carry out a full feasibility study into resettlement under British administration. Over ten months, a team of lawyers, economists, environmental scientists, and engineers examined geography, climate, infrastructure, and governance. They consulted Chagossian communities in Crawley, Manchester, Mauritius, and the Seychelles, and spent a week surveying Diego Garcia and 13 outer islands. Their approach was deliberately neutral, but their conclusion was unambiguous. There are no insurmountable legal, environmental or logistical barriers to resettlement. The obstacles are political, not practical.

KPMG found that the 2004 BIOT Constitution, drafted for an uninhabited territory, would need amendment to reintroduce residency rights, local governance and environmental oversight. But these changes could be made easily by Order in Council. Crucially, resettlement would not breach Britain’s obligations to the United States, with whom it shares a military base. The 1966 UK-US agreement governing Diego Garcia is flexible, and other territories such as Ascension Island already balance military and civilian life successfully. A resettled BIOT under British administration would therefore remain fully compatible with our defence partnership. The missing ingredient, then as now, is political will.

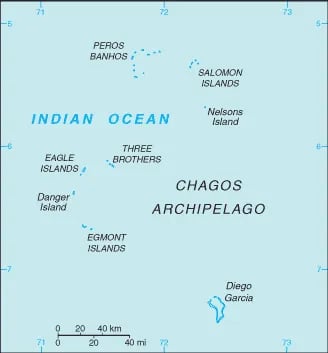

A map of the Chagos Archipelago

The study devoted significant analysis to the environmental question. Fourteen islands were assessed for elevation, soil, water supply, and climate vulnerability. While the islands are low-lying, several, including Diego Garcia, possess freshwater lenses, arable soils, and safe anchorable. Coastal protection would be required, but manageable with modern engineering. Consultations revealed that the Chagossians themselves are deeply committed environmentalists. KPMG proposed a model of small, energy-efficient “eco-resettlement” integrated with marine conservation and research. Far from undermining the environment, resettlement could enhance stewardship of one of the world’s richest marine ecosystems, an outcome which aligns perfectly with the UK’s Blue Belt conservation programme.

On the practical side, engineers found that a pilot community of around 150 people could be established quickly using modular construction, renewable energy and local labour. Much of the necessary infrastructure, including runways, desalination, power and jetties already exist on Diego Garcia. The economics were equally as compelling. KPMG modelled three scenarios: a large community of 1,500, a medium settlement of 500, and a pilot of 150 people. Capital costs ranged from £63 million to £414 million for full resettlement. Even with the most ambitious plan, updated for inflation, would amount roughly to £574 million, a rounding error in the UK national budget. The study also identified long-term revenue opportunities, including eco-tourism, fishing, conservation work, and BIOT Government services such as research licences, stamps, and the popular .io internet domain. It even listed potential funding partners, including the European Investment Bank and private conservation initiatives. This is not a drain on the taxpayers but a chance to create a showcase for sustainable British development at a fraction of the cost of the transfer deal with Mauritius.

Above all, the report records the voices of the Chagossians themselves; voices that have been ignored since 1965, and continue to be ignored today. Across the UK, the Seychelles, and Mauritius, their message was unanimous - they wish to return permanently, not as visitors. They aspire to modern living standards, with schools, clinics, internet, and are ready to build them. Many are trained as tradespeople, public servants, and professionals. They are not dependent, they are determined.

Members of the British Chagossian community unite against the deal in Manchester

Taken together, the KPMG findings outline a practical and ethical path with a small, environmentally responsible British settlement on Diego Garcia and the outer islands, in partnership with the US/UK facility, expanding gradually as self-sufficiency grows. Such a plan would honour Britain’s moral duty, maintain our strategic presence in the Indo-Pacific, and preserve a unique marine environment. The Government’s current approach of negotiating away sovereignty without consultation fails every test of transparency, accountability and good governance. Peers should insist that the full KPMG study be considered, that the Chagossians be given a genuine voice through a referendum, and the handover deal be axed.

If the UK truly believes in responsible global leadership, we cannot give away what we have not even tried to restore, against the wishes of those who call the islands home but shamefully live in exile. The evidence is clear: resettlement is feasible. The only question is whether our leaders have the courage to act on it.